Rijeka, the main port city for northern Croatia, used to be the Austro-Hungarian seaport known as Fiume, and is a stubbornly non-tourist city fabulously slagged off in almost every guidebook to Croatia ever written. It is a working port and working class metropolis by the sea - if you want beaches, go elsewhere. On the other hand, it is one of the most fascinating and unique destinations that nobody ever goes to on the Croatian coast. Rijeka isn't an easy visit: it doesn't expect people to stay, and accomodations are scarce and pricier than at resorts along the sea. Everything else - food, and the surprisingly lively night life scene - is far cheaper.

Who needs night life when you have street life. We caught a park festival featuring guys dressed up as clowns and animals while contestants dived into a deep pool full of sudsy water groping around to pick up bananas and win prizes. Surreal, yes, but in a 1960s Italian film kind of way. Rijeka is famous for its local rock scene: we saw the

Rijeka band Let 3 at the A38 a month ago and they just about blew even the most jaded rock snobs away when they finally stripped for their final number - played naked with dog muzzles covering their family jewels and with roses stuck in their behinds.

Controlled by the Hapsburgs since 1466, Rijeka came under Hungarian control in 1870. Although the population was primarily Croatian and Italian, a prosperous Hungarian middle class set roots down here in the years before World War 1. In 1912 the future Hungarian communist politician and party leader

János Kádár was born in then Rijeka as Giovanni Czermanik. Former New Yiork Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia worked at the U.S. consulate here from 1904 to 1906, allegedly playing for the Rijeka football club while here.

Hungarians tend to get nostalgic about the "loss of Fiume" - the only sea port they ever had control of, but after World War I things really started to go pear-shaped. After a brief Italian occupation, in November 1918 an international force of French, British and American troops occupied the city. Italy claimed Rijeka on the fact that Italians were the largest single nationality within the city. Croats made up most of the remainder and were also a majority in the surrounding area, including the neighbouring town of Sušak. On September 10, 1919, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was dissolved.

Two days later a force of Italian nationalist irregulars led by the writer Gabriele d'Annunzio seized control of the city. Eventually Italy and Yugoslavia concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, under which Rijeka/Fiume was to be an independent state, the

Free State of Fiume. In 1924, however, Rijeka was annexed by the Italian Fascists to Italy itself, and was only ceded to Yudoslavia in 1947. (Given that I am going to be doing a gig in Gdansk/Sopot, Poland on July 22 with Di Nayes, this makes two former Free Port States I will be visiting this summer. I feel like

I ought to annex some territory or something.) Another result is that while Istria feels like a lost bit of the Italian countryside, Rijeka/Fiume feels like nothing so much as a funky, down at the heels Italian port city that just happens to speak Croatian.

Rijeka is where you can really sense the meeting of Italian and Balkan cuisine. This isn't a tourist town, and we chose our dinner spot based on the "how many families are happily chowing down here" method of restaurant selection. And they were chowing down at a grill joint offering cevapcici and pljeskavica just next door to a tapas bar highly recommended by our associates at Time Out Travel Guides. The Tapas joint was deserted. The Cevap joint was packed. A difficult decision.

Cevap

Cevap is the Balkan/Yugo version of the Turkish word "kebap" i.e., kebab. Essentially it is a mixture of beef and sometimes lamb (more beef in Croatia, more lamb in Bosnia and Macedonia) rolled into those tasty little skinless sausage patties we know in Turkish as

köfte. I discovered at home that I could not make these using ground beef bought at the butcher's (or in our case, Tesco) because the grind was too coarse. The trick is to pulverize the already ground beef into a paste using a meat tenderizing hammer (hammer the handful of meat inside a plastic bag so you don't paint the room in

explosive meat color) then season and form into thumbsize rolls. Smash the ground meat mixture into a dish-sized patty and the result is a pleskavica (or

pljeskavica as the call it in

je-kavian Croat) These may be served in a fluffy flat bread called

lepinje, which can very rarely be found in Hungary as

lepény.

Ignore the recent

cevap recipe given at Chew.hu which includes pork - pork doesn't belong anywhere near a cevap or pleskavica. For one thing, it would fall apart (ground pork needs a binder or a sausage casing to form a stable patty.) For another thing... it would taste like a Tesco cevap, and we wouldn't want that. (Or, to paraphrase Frank Zappa

"Is that a real cevap or is that a Tesco cevap?") If you are hankering for a cevap or pleskavica in Budapest you will find them either at the

Kafana serb resturant or at the

Jelen Biszto behind the Corvin Department Store at Blaha Lujza ter in Pest.

Kafana is more elegant, but the Jelen accurately replicates the

lepinje sandwich style. (The orange stuff seen below is

ajvar - a mild red pepper paste condiment.)

In terms of interest,

pleskavica and

cevapcici are among the two items that lead the pack in leading readers to this blog from Google.

Welcome to our blog, hungry Balkanoid appetites of the Internets! (The most common searches leading to

Dumneazu are to the "

Yidn Mit Pixels" page about B&H photo in NY, the

Fröhlich Cukrászda post,

the Kádár Étkezde post, with many, many Romanians visiting the posts on

Vioara cu Goarne - possibly because those posts have earned themselves their own Romanian Wikipedia entry. Obviously, the world is hungrier for more info about weird bastard trumpet fiddles than we knew about.

One final word: Croatia is still not conforming to the EU rules regarding modern information signs. As can be seen from the sign above (from the beach at Verdula in Pula) you are heartily encouraged to abandon your crippled family members by rolling them downhill into the sea. And this sign (downtown Novigrad) can be interpreted in several ways:

1.

Policemen Not Allowed to Play in Picnic Areas.2.

Free Wifi for Members of Marching Bands!3.

Do Not Attempt to Fly the Cylon Base Star by Yourself!

We would also like take the time to aknowledge the ugly little shitbird who served as our Hungarian State Railway conductor on the couchette car back to Budapest from Rijeka. As our train was to leave at 20 minutes after midnight on Sunday, Fumie asked the conductor about our seats only to be told that the ticket was for Sunday night, not Saturday night, and no amount of discussion would get him to admit that 00.20 AM actually was on a Sunday. He was pretending not to understand Fumie's (quite fluent) Hungarian when I strolled up. "But you are not on the reservation list!" After calmly conversing with this transparently corrupt retard (

my sincere apologies to all the honest and genuinely hard working retards out there...but one bad apple spoils it for everyone) I asked "So how do we solve this problem?" "

Well, it can be solved... with a tenner!" 10,000 Forints... about 40 Euros, this after we paid 9 Euros for our valid couchette and knowing that a couchette bed costs only 14 Euros without reservations. I said calmly "

rendben" - fine. He led us onto the train and proceeded to warn us about all the dangers - thieves mostly - that awaited us in Zagreb station. In twenty years of riding every cattle car in the Balkans the only actual thieves I ever encountered on a train were within ten kilometers of Budapest.

Once on the train I had no intention of coughing up the bribe to this greedy little ogre, but faced by two speakers of Hungarian instead of one he lost face, and soon the little MAV geek popped his misshapened head into the cabin to announce "Oh! I found you on the list of reservations! Must have been looking at the older list!" So no, we will not bother reporting your pathetic attempt at extortion to the already pathetically corrupt MAV management in Hungary. They'll all be on strike in a week or so anyway. Nobody knows why. Nobody cares, either.

I am back in Budapest for a few days between sessions at the Weimar Yiddish Music festival. Di Naye K is heading up that way next week to do a concert on July 24th, and then we are providing music for the dance workshops - Klezmer in the morning for Yiddish dance (taught by our own Budapest Klezmer Dancing Queen Sue Foy, Michael Alpert from Brave Old World, and Zev Feldman) and Transylvanian Gypsy dancing in the afternoon with Florin Kodoban, the fiddler from the Palatka band.

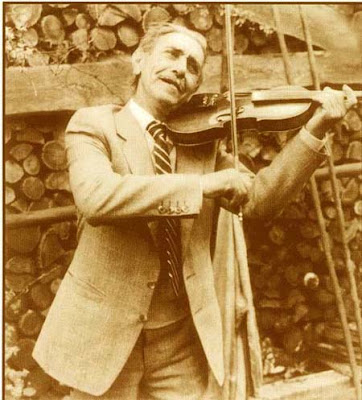

I am back in Budapest for a few days between sessions at the Weimar Yiddish Music festival. Di Naye K is heading up that way next week to do a concert on July 24th, and then we are providing music for the dance workshops - Klezmer in the morning for Yiddish dance (taught by our own Budapest Klezmer Dancing Queen Sue Foy, Michael Alpert from Brave Old World, and Zev Feldman) and Transylvanian Gypsy dancing in the afternoon with Florin Kodoban, the fiddler from the Palatka band. In Palatka, a small village in the Mezőség (or Câmpia Transilvaniei) twenty kilometers east of Cluj, the Kodoban, Radak, and Macsingo families have provided the music for the mixed ethnic populations of the Mezőség region for genersations. Palatka's virtual isolation has allowed it to preserve a particularly rich dance tradtion and an archaic style of fiddle band music, rich in ornamentation, lop-sided rythyms, and a dissonant sense of harmonizing modal melodies against major chords played on the three stringed, flat bridged viola known in Transylvania as the kontra. [The black and white photos of the Palatka musicians are from the website of the noted Hungarian photographer and musician Bela Kasa.]

In Palatka, a small village in the Mezőség (or Câmpia Transilvaniei) twenty kilometers east of Cluj, the Kodoban, Radak, and Macsingo families have provided the music for the mixed ethnic populations of the Mezőség region for genersations. Palatka's virtual isolation has allowed it to preserve a particularly rich dance tradtion and an archaic style of fiddle band music, rich in ornamentation, lop-sided rythyms, and a dissonant sense of harmonizing modal melodies against major chords played on the three stringed, flat bridged viola known in Transylvania as the kontra. [The black and white photos of the Palatka musicians are from the website of the noted Hungarian photographer and musician Bela Kasa.] Of course, there was always a question about "which Gypsy dance" to which the answer is there is no single Roma dance tradition. The dances from Transylvania, however, are one of the few that are done to an instrumental music played by Roma for Roma, known as ţiganeşti in Romanian and cigány tanc in Hungarian, or basically, romani khelipe in Romani.

Of course, there was always a question about "which Gypsy dance" to which the answer is there is no single Roma dance tradition. The dances from Transylvania, however, are one of the few that are done to an instrumental music played by Roma for Roma, known as ţiganeşti in Romanian and cigány tanc in Hungarian, or basically, romani khelipe in Romani. One of the main features of Romani dance, in contrast to the non-Gypsy gadjo population, is that the Roma maintain a much stricter separation and definition of gender roles between men and women. The Roma style of dance reflects this: men and women dance in couples but without touching or holding, for the most part. In the Mezőség a "dance cycle" begins with slow dances and can last over a half hour before ending with twenty minutes of fast csardas dances. The Gypsy dance cycles include some couple dances in which the couples are holding each other (such as the slow "lassu ciganytanc") but they then either skip or sit out the middle tempo dances until the final fast dances, during which the Roma men show off in a far more improvisiational manner than the non-Gypsy dancers.

One of the main features of Romani dance, in contrast to the non-Gypsy gadjo population, is that the Roma maintain a much stricter separation and definition of gender roles between men and women. The Roma style of dance reflects this: men and women dance in couples but without touching or holding, for the most part. In the Mezőség a "dance cycle" begins with slow dances and can last over a half hour before ending with twenty minutes of fast csardas dances. The Gypsy dance cycles include some couple dances in which the couples are holding each other (such as the slow "lassu ciganytanc") but they then either skip or sit out the middle tempo dances until the final fast dances, during which the Roma men show off in a far more improvisiational manner than the non-Gypsy dancers. The middle tempo dances done by non-Gypsy peasants usually feature a lot of mixed couple figures that intertwine the dancers bodies - movements which are not considered proper by Romani attitudes towards gender interaction. It should be interesting to teach Roma dance to folk dancers - we are happy to teach women the men's steps and vice versa, but the dancers would never get a chance to use those figures in anyreal-life situation among Roma involving dance. It is a pretty strict rule in Roma society that gender roles are never reversed.

The middle tempo dances done by non-Gypsy peasants usually feature a lot of mixed couple figures that intertwine the dancers bodies - movements which are not considered proper by Romani attitudes towards gender interaction. It should be interesting to teach Roma dance to folk dancers - we are happy to teach women the men's steps and vice versa, but the dancers would never get a chance to use those figures in anyreal-life situation among Roma involving dance. It is a pretty strict rule in Roma society that gender roles are never reversed. Part of the seminar session at Weimar concerned the interaction of Gypsy and Jewish musicians in eastern Europe. Festival director Alan Bern brought lautar musicians Adam Stinga and Marin Bunea (and Marin Recean, clarinetist) from Chisinau, Moldova and our own Kalman Balogh and Csaba Novak from Budapest for the Roma music project. Kalman brought along several bottles of top shelf Hungarian fruit brandy to liven things up. Look! Why is everybody smiling?

Part of the seminar session at Weimar concerned the interaction of Gypsy and Jewish musicians in eastern Europe. Festival director Alan Bern brought lautar musicians Adam Stinga and Marin Bunea (and Marin Recean, clarinetist) from Chisinau, Moldova and our own Kalman Balogh and Csaba Novak from Budapest for the Roma music project. Kalman brought along several bottles of top shelf Hungarian fruit brandy to liven things up. Look! Why is everybody smiling? My Man in Austin, Mark Rubin, was on hand to handle low notes on tuba and bass. Mark is one of the finest people I know in the Klezmer scene, and also one of the funniest bastards on the face of the planet. He also has a tattoo on his arm of Moses recieving the comandments at Mt. Sinai. Unkosher, yes, but eminently cool. Did I mention that Mark is a Big Hungry Boy?

My Man in Austin, Mark Rubin, was on hand to handle low notes on tuba and bass. Mark is one of the finest people I know in the Klezmer scene, and also one of the funniest bastards on the face of the planet. He also has a tattoo on his arm of Moses recieving the comandments at Mt. Sinai. Unkosher, yes, but eminently cool. Did I mention that Mark is a Big Hungry Boy?  Another old friend from Budapest at Weimar was Claude Cahn, previously of the European Roma rights Center and now working for the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions in Geneva. Claude spoke to the seminar about Roma Rights in Europe, but most of the time he held a special seminar entitled "Jewish-Roma Babies in Europe: Look at These Hundreds of Pictures of My Baby Daughter Sarah Kali Cahn" Sarah shares her mother Cosmina's beautiful eyes and Romani gracefulness, while from her father she seems to have inherited both intelligence and a whopping huge frigging Jewish shnozzola.

Another old friend from Budapest at Weimar was Claude Cahn, previously of the European Roma rights Center and now working for the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions in Geneva. Claude spoke to the seminar about Roma Rights in Europe, but most of the time he held a special seminar entitled "Jewish-Roma Babies in Europe: Look at These Hundreds of Pictures of My Baby Daughter Sarah Kali Cahn" Sarah shares her mother Cosmina's beautiful eyes and Romani gracefulness, while from her father she seems to have inherited both intelligence and a whopping huge frigging Jewish shnozzola. Weimar, as you all know, is where the Germans learned to make money worthless. Nevertheless the town is as cute as a German city can be, and crawling with tourists. It is in East Germany, which means the food is almost as bad as Finnish food (which is pretty hard to compete with, so let's give our Ossie friends an A for effort!) and the service makes Hungarian waiters seem like busy bees. On average, one waits for well over an hour after ordering a meal to get served. During that hour I am usually regaled by Mark Rubin loudly threatening to crush the wait staff to death beneath his massive buttocks.

Weimar, as you all know, is where the Germans learned to make money worthless. Nevertheless the town is as cute as a German city can be, and crawling with tourists. It is in East Germany, which means the food is almost as bad as Finnish food (which is pretty hard to compete with, so let's give our Ossie friends an A for effort!) and the service makes Hungarian waiters seem like busy bees. On average, one waits for well over an hour after ordering a meal to get served. During that hour I am usually regaled by Mark Rubin loudly threatening to crush the wait staff to death beneath his massive buttocks. Our accomodation, however, was great: the Hotel Leonardo in Weimar gets my custom whenever I head through town with a wallet stuffed impossibly full of Euros. And they do, in fact, make a room service cheeseburger that knocked my socks off. I didn't feel inspired to photograph much of the East German food I encountered. It was mostly brown, and looked like, well, brown stuff. This was probably the first time in my life that I ordered room service... heck, it wasn't even that expensive. And you can't get a good burger in Hungary at all. I salute you, Masterful Burger Chef of the Hotel Leonardo Weimar!

Our accomodation, however, was great: the Hotel Leonardo in Weimar gets my custom whenever I head through town with a wallet stuffed impossibly full of Euros. And they do, in fact, make a room service cheeseburger that knocked my socks off. I didn't feel inspired to photograph much of the East German food I encountered. It was mostly brown, and looked like, well, brown stuff. This was probably the first time in my life that I ordered room service... heck, it wasn't even that expensive. And you can't get a good burger in Hungary at all. I salute you, Masterful Burger Chef of the Hotel Leonardo Weimar!

This year director Alan Bern has focused on the role of Jewish and Roma musicians as "the Others" in the history of European music, and Alan has asssembled a number of participants to talk about the history and culture of "music on the perimeters" of the main culture. Next week is the conference/seminar/film component of the summer program. Later Di Nayes will return to Weimar with Florin Kodoban from Palatka to do a concert and a week of dance workshops - playing for the Klezmer dance workshops in the morning, and Transylvanian "Ţiganeşti" Gypsy style dances in the afternoon. I'm looking forward to playing with Florin - I knew his late father, Márton, well and Puma and the boys in the band have been playing with the Palatka band on and off since the 1970s. Jake Shulmen-Ment is planning to be there from NYC. Jake has been turning into the prodigal ace of NY fiddlers who play both klezmer and Transylvanian... so this should be fun. I'm hoping to do a few very early Moldavian lautar songs from the early 1800s mixed up with some older Klezmer stuff.

This year director Alan Bern has focused on the role of Jewish and Roma musicians as "the Others" in the history of European music, and Alan has asssembled a number of participants to talk about the history and culture of "music on the perimeters" of the main culture. Next week is the conference/seminar/film component of the summer program. Later Di Nayes will return to Weimar with Florin Kodoban from Palatka to do a concert and a week of dance workshops - playing for the Klezmer dance workshops in the morning, and Transylvanian "Ţiganeşti" Gypsy style dances in the afternoon. I'm looking forward to playing with Florin - I knew his late father, Márton, well and Puma and the boys in the band have been playing with the Palatka band on and off since the 1970s. Jake Shulmen-Ment is planning to be there from NYC. Jake has been turning into the prodigal ace of NY fiddlers who play both klezmer and Transylvanian... so this should be fun. I'm hoping to do a few very early Moldavian lautar songs from the early 1800s mixed up with some older Klezmer stuff. Jewish musicians have been interacting with Gypsy musicians for over three hundred years in East Europe. Music - at least popular and wedding music - has traditionally been performed by hereditary dynasties of musicians, whether 'klezmer" families of Jews, or "lautar" (or "bashaldar") familes of Roma. Over the years that I have been collecting Jewish instrumental music in East Europe, my main sources have been Gypsy musicians who had once played for Jews and who maintained a repetoire of Jewish dances. This is mainly because in a small town or village, the local non-Gypsy musicians can usually play the music of their own ethnic group, but were rarely called on as professionals to play the music of any other ethnic group. Sadly, that generation is almost gone... One of my best teachers and sources was Gheorghe "Ionnei" Covaci from the vilage of Ieud in Maramures. He passed on in 2002.

Jewish musicians have been interacting with Gypsy musicians for over three hundred years in East Europe. Music - at least popular and wedding music - has traditionally been performed by hereditary dynasties of musicians, whether 'klezmer" families of Jews, or "lautar" (or "bashaldar") familes of Roma. Over the years that I have been collecting Jewish instrumental music in East Europe, my main sources have been Gypsy musicians who had once played for Jews and who maintained a repetoire of Jewish dances. This is mainly because in a small town or village, the local non-Gypsy musicians can usually play the music of their own ethnic group, but were rarely called on as professionals to play the music of any other ethnic group. Sadly, that generation is almost gone... One of my best teachers and sources was Gheorghe "Ionnei" Covaci from the vilage of Ieud in Maramures. He passed on in 2002.

In the Austro-Hungarian regions and Moldavia, however, the tsekh system was weaker or non-existent. In these areas a Jewish band would often fill its ranks with extra musicians from the local Roma musician communities. Kid fiddlers were cheap. Maramures fiddler Cheorghe Covaci "Cioata" once told me that pre WWII Jewish band leaders used to pay him "with cake." His cousin, Rajna Covaci told me the same thing. (My own band wouldn't take well to that.) After the Holocaust, in many regions such as Karpatalja, certain Gypsy musicians became the preferred musicians for the Jewish community, as did the Fiddler Manyo Csernovec from Tjaciv, Ukraine, the father of the musicians in today's

In the Austro-Hungarian regions and Moldavia, however, the tsekh system was weaker or non-existent. In these areas a Jewish band would often fill its ranks with extra musicians from the local Roma musician communities. Kid fiddlers were cheap. Maramures fiddler Cheorghe Covaci "Cioata" once told me that pre WWII Jewish band leaders used to pay him "with cake." His cousin, Rajna Covaci told me the same thing. (My own band wouldn't take well to that.) After the Holocaust, in many regions such as Karpatalja, certain Gypsy musicians became the preferred musicians for the Jewish community, as did the Fiddler Manyo Csernovec from Tjaciv, Ukraine, the father of the musicians in today's  In the last couple of years many of the last generation of klezmer musicians who had learned their music as part of a Yiddish upbringing with ties to a fast vanishing "Old Country" have passed on. Paul Pincus, Howie Lees,

In the last couple of years many of the last generation of klezmer musicians who had learned their music as part of a Yiddish upbringing with ties to a fast vanishing "Old Country" have passed on. Paul Pincus, Howie Lees,  On my last trip collecting music in Maramures, in Romania, I was still able to find Gypsy musicians who knew a repetoire of local Jewish music. Besides Ionu (who locally goes by the nickname "Paganini") there was also Gheorghe Urecche ("The Ear") who learned his tunes from his father, who had been a cross-border smuggler in league with a Jewish musician remembered as "Benzine." Let that be a warning to those named Ben-Zion. Historical folk memory can be merciless.

On my last trip collecting music in Maramures, in Romania, I was still able to find Gypsy musicians who knew a repetoire of local Jewish music. Besides Ionu (who locally goes by the nickname "Paganini") there was also Gheorghe Urecche ("The Ear") who learned his tunes from his father, who had been a cross-border smuggler in league with a Jewish musician remembered as "Benzine." Let that be a warning to those named Ben-Zion. Historical folk memory can be merciless.

Who needs night life when you have street life. We caught a park festival featuring guys dressed up as clowns and animals while contestants dived into a deep pool full of sudsy water groping around to pick up bananas and win prizes. Surreal, yes, but in a 1960s Italian film kind of way. Rijeka is famous for its local rock scene: we saw the

Who needs night life when you have street life. We caught a park festival featuring guys dressed up as clowns and animals while contestants dived into a deep pool full of sudsy water groping around to pick up bananas and win prizes. Surreal, yes, but in a 1960s Italian film kind of way. Rijeka is famous for its local rock scene: we saw the

Hungarians tend to get nostalgic about the "loss of Fiume" - the only sea port they ever had control of, but after World War I things really started to go pear-shaped. After a brief Italian occupation, in November 1918 an international force of French, British and American troops occupied the city. Italy claimed Rijeka on the fact that Italians were the largest single nationality within the city. Croats made up most of the remainder and were also a majority in the surrounding area, including the neighbouring town of Sušak. On September 10, 1919, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was dissolved.

Hungarians tend to get nostalgic about the "loss of Fiume" - the only sea port they ever had control of, but after World War I things really started to go pear-shaped. After a brief Italian occupation, in November 1918 an international force of French, British and American troops occupied the city. Italy claimed Rijeka on the fact that Italians were the largest single nationality within the city. Croats made up most of the remainder and were also a majority in the surrounding area, including the neighbouring town of Sušak. On September 10, 1919, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was dissolved.  Two days later a force of Italian nationalist irregulars led by the writer Gabriele d'Annunzio seized control of the city. Eventually Italy and Yugoslavia concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, under which Rijeka/Fiume was to be an independent state, the

Two days later a force of Italian nationalist irregulars led by the writer Gabriele d'Annunzio seized control of the city. Eventually Italy and Yugoslavia concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, under which Rijeka/Fiume was to be an independent state, the  Rijeka is where you can really sense the meeting of Italian and Balkan cuisine. This isn't a tourist town, and we chose our dinner spot based on the "how many families are happily chowing down here" method of restaurant selection. And they were chowing down at a grill joint offering cevapcici and pljeskavica just next door to a tapas bar highly recommended by our associates at Time Out Travel Guides. The Tapas joint was deserted. The Cevap joint was packed. A difficult decision.

Rijeka is where you can really sense the meeting of Italian and Balkan cuisine. This isn't a tourist town, and we chose our dinner spot based on the "how many families are happily chowing down here" method of restaurant selection. And they were chowing down at a grill joint offering cevapcici and pljeskavica just next door to a tapas bar highly recommended by our associates at Time Out Travel Guides. The Tapas joint was deserted. The Cevap joint was packed. A difficult decision. Cevap is the Balkan/Yugo version of the Turkish word "kebap" i.e., kebab. Essentially it is a mixture of beef and sometimes lamb (more beef in Croatia, more lamb in Bosnia and Macedonia) rolled into those tasty little skinless sausage patties we know in Turkish as köfte. I discovered at home that I could not make these using ground beef bought at the butcher's (or in our case, Tesco) because the grind was too coarse. The trick is to pulverize the already ground beef into a paste using a meat tenderizing hammer (hammer the handful of meat inside a plastic bag so you don't paint the room in explosive meat color) then season and form into thumbsize rolls. Smash the ground meat mixture into a dish-sized patty and the result is a pleskavica (or pljeskavica as the call it in je-kavian Croat) These may be served in a fluffy flat bread called lepinje, which can very rarely be found in Hungary as lepény.

Cevap is the Balkan/Yugo version of the Turkish word "kebap" i.e., kebab. Essentially it is a mixture of beef and sometimes lamb (more beef in Croatia, more lamb in Bosnia and Macedonia) rolled into those tasty little skinless sausage patties we know in Turkish as köfte. I discovered at home that I could not make these using ground beef bought at the butcher's (or in our case, Tesco) because the grind was too coarse. The trick is to pulverize the already ground beef into a paste using a meat tenderizing hammer (hammer the handful of meat inside a plastic bag so you don't paint the room in explosive meat color) then season and form into thumbsize rolls. Smash the ground meat mixture into a dish-sized patty and the result is a pleskavica (or pljeskavica as the call it in je-kavian Croat) These may be served in a fluffy flat bread called lepinje, which can very rarely be found in Hungary as lepény.  Ignore the recent

Ignore the recent  In terms of interest,

In terms of interest,

Once on the train I had no intention of coughing up the bribe to this greedy little ogre, but faced by two speakers of Hungarian instead of one he lost face, and soon the little MAV geek popped his misshapened head into the cabin to announce "Oh! I found you on the list of reservations! Must have been looking at the older list!" So no, we will not bother reporting your pathetic attempt at extortion to the already pathetically corrupt MAV management in Hungary. They'll all be on strike in a week or so anyway. Nobody knows why. Nobody cares, either.

Once on the train I had no intention of coughing up the bribe to this greedy little ogre, but faced by two speakers of Hungarian instead of one he lost face, and soon the little MAV geek popped his misshapened head into the cabin to announce "Oh! I found you on the list of reservations! Must have been looking at the older list!" So no, we will not bother reporting your pathetic attempt at extortion to the already pathetically corrupt MAV management in Hungary. They'll all be on strike in a week or so anyway. Nobody knows why. Nobody cares, either.

After arriving at the bus station, we checked with a private tourist office next door, and soon 50 Euros got us a beautiful private apartment twenty meters away from the sea. Air conditioning! Kitchen! Satelite TV! Croatia regulates its tourist business carefully, so you can trust these apartment rentals for quality - the rate per person comes to the same as a dorm bed in a youth hostel. No contest...

After arriving at the bus station, we checked with a private tourist office next door, and soon 50 Euros got us a beautiful private apartment twenty meters away from the sea. Air conditioning! Kitchen! Satelite TV! Croatia regulates its tourist business carefully, so you can trust these apartment rentals for quality - the rate per person comes to the same as a dorm bed in a youth hostel. No contest...  Now, I am not the beachiest person on the block, but to be honest, the Istrian coast has pretty but uninviting beaches... rocky, stony, bring a pair of rubber beach shoes. At Novigrad, at least, the beach has a series of stone approaches and child friendly inner inlets protected from the open sea.

Now, I am not the beachiest person on the block, but to be honest, the Istrian coast has pretty but uninviting beaches... rocky, stony, bring a pair of rubber beach shoes. At Novigrad, at least, the beach has a series of stone approaches and child friendly inner inlets protected from the open sea. And nobody is ever far from a beer. I had my first beer in five months here... and probably my last beer for another five months. Actually, I dropped my low-carb diet while in Istria and was surprised that I didn't blow up like a puffer fish in response to eating pasta and pizza after months of going without.

And nobody is ever far from a beer. I had my first beer in five months here... and probably my last beer for another five months. Actually, I dropped my low-carb diet while in Istria and was surprised that I didn't blow up like a puffer fish in response to eating pasta and pizza after months of going without. I mean, how can you say no to a seafood risotto like this? As far as restaurant dining is concerned, Istria is definately a dialect of Italian cuisine, and the Adriatic this far north is known for its slimey crawly sea bugs. Grilled sardines are an affordable specialty, but almost any other scaled fish will send you to a bank officer before the waitress arrives. The Adriatic, indeed, the entire Mediterranean sea, is slowly being fished out and supplies of white-fleshed fish are at an expensive premium. Seafood, however, is within reach of the average eater, perhaps in a risotto...

I mean, how can you say no to a seafood risotto like this? As far as restaurant dining is concerned, Istria is definately a dialect of Italian cuisine, and the Adriatic this far north is known for its slimey crawly sea bugs. Grilled sardines are an affordable specialty, but almost any other scaled fish will send you to a bank officer before the waitress arrives. The Adriatic, indeed, the entire Mediterranean sea, is slowly being fished out and supplies of white-fleshed fish are at an expensive premium. Seafood, however, is within reach of the average eater, perhaps in a risotto... Or in a pasta dish, as in this seafood tagliatelle for two (20 Euros for a portion for two) at the

Or in a pasta dish, as in this seafood tagliatelle for two (20 Euros for a portion for two) at the  We followed this with a plate of fried squid. Kalamari are always plentiful and are usually grilled and doused with olive oil, or fried in a light coating of flour. The Croatian coast is a paradise for cephalopod lovers... octopus salads, cuttlefish risotto, or squids are on just about every menu. Apparently, the BBC says that squids are now the one species which is the most prevalent biomass of any living critter on earth. And they only live for 180 days. And they can comunicate by varying their skin color patterns and thus show signs of intelligence. And man, they taste gooood....

We followed this with a plate of fried squid. Kalamari are always plentiful and are usually grilled and doused with olive oil, or fried in a light coating of flour. The Croatian coast is a paradise for cephalopod lovers... octopus salads, cuttlefish risotto, or squids are on just about every menu. Apparently, the BBC says that squids are now the one species which is the most prevalent biomass of any living critter on earth. And they only live for 180 days. And they can comunicate by varying their skin color patterns and thus show signs of intelligence. And man, they taste gooood.... And then to the town square, where the cafes were all set up with wide screen televisions to watch the semi-finals of the European Cup soccer matches.

And then to the town square, where the cafes were all set up with wide screen televisions to watch the semi-finals of the European Cup soccer matches.